By: Sheikh Jawad Habib

Abstract

The migration of Iranian Baloch to the Indian subcontinent represents an important yet understudied chapter of migration history. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, tribes from Baluchistan, Kerman, and Sistan left Iran in search of better economic opportunities and in response to natural disasters and insecurity. In India, they became commonly known as “Balochi,” although they consistently identified themselves as Iranians and gharib-ul-watan (exiled strangers from their homeland). Their livelihoods were primarily based on petty trade, handicrafts, and a nomadic lifestyle. Over time, they integrated into Indian society; however, the commemoration of the martyrdom of Imam Husayn (ʿa) and their Persian-influenced language have continued to preserve their Iranian identity.

This article analyzes the causes of their migration, their socio-linguistic and economic life, the Indian government’s approach towards them, and their contemporary situation.

Historical Foundations of Migration

The migration of Iranian Baloch to India can be attributed to three main factors:

- Tribal conflicts and unrest in Iran’s eastern borderlands.

- Repeated famines and droughts.

- Economic opportunities in the thriving urban markets of India.

Social and Linguistic Identity

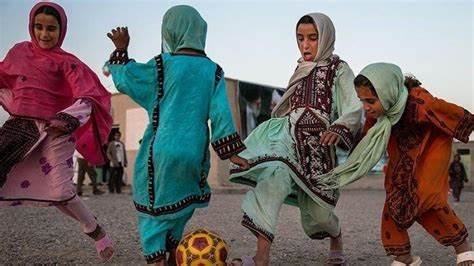

In Iran, these groups were referred to as “nomads” or sometimes “Gypsies,” but in India they came to be known as “Balochi.” Their original languages were Persian and Balochi, but over time they adopted Urdu and Hindi. Religiously, they remained Muslim, and their religious gatherings—especially the commemoration of the martyrdom of Imam Husayn (ʿa)—remain a defining marker of their collective identity.

Geographic Settlement

Today, Iranian Baloch communities are dispersed across several Indian states, including:

- Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, and Bihar (mostly in peripheral and semi-urban areas).

- Gujarat and Maharashtra (in commercial and port cities).

- Madhya Pradesh, particularly in the city of Bhopal, where their tribal chief resides and where a prominent Hussainiya serves as their religious and social center.

- Southern India (Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh).

- Eastern India (West Bengal).

Many Baloch families settled near railway stations in order to sustain their small-scale trading activities.

Economy and Occupations

Their economy has historically been informal, based on:

- Handicrafts.

- Street vending and itinerant trade.

- Small-scale metal work (copper and iron).

- Women’s involvement in fortune-telling and performing arts.

This informal economic pattern pushed them to the margins of Indian society and often drew comparisons with local nomadic groups.

Contemporary Situation

By the twentieth century, some segments of this community became more settled in urban areas and took up relatively stable employment. Today, their population is estimated at around 10,000 individuals across India. Persian, though heavily mixed with Urdu and Hindi, is still used, while the mourning rituals of Muharram remain the most prominent aspect of their cultural and religious identity.

The Indian Government’s Approach

The Indian state has generally adopted a policy of non-interference toward the Iranian Baloch:

- They have been legally granted citizenship, though their Iranian origins sometimes subject them to social discrimination.

- They have rarely been included in state development programs, leaving them trapped in poverty and informal economies.

- Education and healthcare facilities are, in principle, available to them, but social vulnerability and economic hardship prevent them from accessing these services fully.

- Their religious and cultural gatherings are tolerated, though they do not receive official support or recognition.

Conclusion

The Iranian Baloch of India have preserved their Iranian roots through language, cultural memory, and religious rituals. Although they have assimilated into Indian society, they remain socially and economically marginalized. The Indian government has generally maintained an attitude of tolerance and civic equality, yet no comprehensive policy has been implemented for their socio-economic uplift. This community therefore requires further academic research, social recognition, and documentation to better understand and preserve their identity and role in the broader history of migration.

References

- Encyclopaedia Iranica, Entry: “Gypsies in Iran and India”. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Qureshi, Regula Burckhardt. The Indian Diaspora: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives. Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Khan, Sharif Shuja. “Nomadic Communities in India: Identity and Marginality.” South Asia Journal of Social Sciences, Vol. 12, 2010.

- Misra, Satish Chandra. Muslim Communities in India. New Delhi: Inter-India Publications, 1985.

- Bhattacharya, P. “Migratory Tribes of Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh.” Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 42, 2001.

- Ali, Daud. “Iranian Influences in Medieval and Modern India.” Cambridge History of India. Cambridge University Press, 2010.

ایرانیان بلوچ مقیم ہند

تحریر: محمد جواد حبیب

خلاصہ

ایرانیان بلوچ کی ہجرت برصغیر کی تاریخ کا ایک اہم مگر کم شناسا باب ہے۔ اٹھارہویں صدی کے آخر اور انیسویں صدی کے اوائل میں بلوچستان، کرمان اور سیستان کے قبائل بہتر معاشی امکانات، قدرتی آفات اور ناامنی سے نجات حاصل کرنے کے لیے برصغیر ہجرت کر گئے۔ ہندوستان میں ان کے لیے ’’بلوچی‘‘ کا نام عام ہوا، لیکن وہ ہمیشہ خود کو ایرانی اور غریب الوطن سمجھتے رہے۔ ان کی معاشی سرگرمیاں زیادہ تر دست فروشی، خانہ بدوش طرزِ حیات اور دستکاری سے وابستہ رہیں۔ وقت گزرنے کے ساتھ وہ ہندوستانی سماج میں مدغم ہوئے، تاہم عزاداریِ سیدالشہداء امام حسینؑ اور فارسی آمیز زبان آج بھی ان کی ایرانی شناخت کو زندہ رکھے ہوئے ہے۔

یہ مقالہ ان کی ہجرت کی وجوہات، معاشرتی و لسانی پہلوؤں، معیشت، حکومتِ ہند کے رویے اور موجودہ صورتحال کا تجزیہ کرتا ہے۔

ہجرت کی تاریخی بنیادیں

ایرانی بلوچوں کے ہندوستان آنے کے تین بڑے اسباب تھے:

1. ایران کے مشرقی سرحدی علاقوں میں شورشیں اور قبائلی تنازعات۔

2. بار بار آنے والے قحط اور خشک سالی۔

3. برصغیر کے شہروں اور بازاروں میں روزگار کے مواقع۔

سماجی و لسانی شناخت

یہ گروہ ایران میں “عشایر” یا “کولی” کے طور پر جانے جاتے تھے مگر برصغیر میں ’’بلوچی‘‘ کہلائے۔ ان کی اصل زبان فارسی اور بلوچی تھی، مگر وقت کے ساتھ ساتھ انہوں نے اردو اور ہندی کو بھی اپنالیا۔ دینی طور پر وہ مسلمان رہے اور آج بھی ان کے مذہبی اجتماعات، خاص طور پر عزاداریِ سیدالشہداء امام حسینؑ اور دیگر دینی رسومات، ان کی اجتماعی شناخت کا بنیادی حصہ ہیں۔

جغرافیائی استقرار

ایرانی بلوچ آج مختلف ریاستوں میں آباد ہیں، مثلاً:

• راجستھان، اتر پردیش اور بہار کے نواحی علاقے۔

• گجرات اور مہاراشٹر کے تجارتی مراکز۔

• مدھیہ پردیش کے شہر بھوپال میں، جہاں ان کا سردار رہتا ہے اور ایک نمایاں حسینیہ ان کا مذہبی و سماجی مرکز ہے۔

• جنوبی ہند (کرناٹک، تامل ناڈو، آندھرا پردیش) اور مشرقی ہند (مغربی بنگال) میں بھی چھوٹے گروہ موجود ہیں۔

اکثر بلوچ خاندان ریلوے اسٹیشنوں کے قریب بس گئے تاکہ اپنی معاشی سرگرمیوں کو جاری رکھ سکیں۔

معیشت اور پیشے

ان کا بنیادی معاش دستکاری، دست فروشی، لوہے اور تانبے کے کام، اور خانہ بدوش تجارت پر مبنی تھا۔ خواتین فال گیری اور گلی کوچوں میں فنونِ لطیفہ پیش کرنے میں بھی شریک رہتی تھیں۔ یہ غیر رسمی معیشت ان کی سماجی کمزوری اور حاشیے پر رہنے کا سبب بنی۔

موجودہ صورتحال

بیسویں صدی میں ان کا ایک حصہ شہروں میں یکجا ہو کر نسبتاً مستحکم روزگار اپنانے لگا۔ آج ان کی آبادی تقریباً دس ہزار نفوس پر مشتمل ہے۔ زبانِ فارسی اب اردو اور ہندی کے ساتھ خلط ملط ہو گئی ہے، لیکن عزاداریِ محرم ان کی ثقافتی اور دینی شناخت کا سب سے نمایاں پہلو ہے۔

حکومتِ ہند کا رویہ

حکومتِ ہند نے ان کے ساتھ عمومی طور پر غیر مداخلتی پالیسی اپنائی ہے:

• قانونی طور پر انہیں مقامی شہریت دی گئی، مگر ان کی ایرانی شناخت بعض اوقات امتیازی سلوک کا باعث بنتی ہے۔

• حکومتی ترقیاتی اسکیموں میں یہ گروہ شاذ و نادر ہی شامل ہوئے ہیں، جس کے باعث وہ آج بھی غربت اور غیر رسمی معیشت میں پھنسے ہوئے ہیں۔

• تعلیم اور صحت کی سہولتیں اصولاً سب کے لیے کھلی ہیں، لیکن سماجی کمزوری اور معاشی ناتوانی کے باعث وہ ان سے بھرپور فائدہ نہیں اٹھا سکے۔

• ان کے مذہبی اور ثقافتی اجتماعات کو برداشت کیا جاتا ہے، تاہم سرکاری سرپرستی یا فروغ موجود نہیں۔

نتیجہ

ایرانی بلوچ مقیم ہند اپنی تاریخ، زبان اور مذہبی رسومات کے ذریعے اپنی ایرانی جڑوں کو آج بھی محفوظ رکھے ہوئے ہیں۔ اگرچہ وہ ہندوستانی سماج میں مدغم ہو چکے ہیں، لیکن سماجی اور معاشی لحاظ سے محروم اور حاشیے پر ہیں۔ حکومتِ ہند نے ان کے ساتھ برداشت اور شہری برابری کا رویہ تو اپنایا ہے، لیکن ان کی ترقی کے لیے کوئی جامع پالیسی سامنے نہیں آئی۔ یہ طبقہ مزید تحقیق، سماجی توجہ اور تاریخی دستاویزات کا متقاضی ہے تاکہ ان کی شناخت اور کردار کو بہتر طور پر سمجھا جا سکے۔

حوالہ جات / ریفرنسز

1. Encyclopaedia Iranica, Entry: “Gypsies in Iran and India”. New York: Columbia University Press.

2. Qureshi, Regula Burckhardt. The Indian Diaspora: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives. Oxford University Press, 1996.

3. Khan, Sharif Shuja. “Nomadic Communities in India: Identity and Marginality.” South Asia Journal of Social Sciences, Vol. 12, 2010.

4. Misra, Satish Chandra. Muslim Communities in India. New Delhi: Inter-India Publications, 1985.

5. Bhattacharya, P. “Migratory Tribes of Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh.” Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 42, 2001.

6. Ali, Daud. “Iranian Influences in Medieval and Modern India.” Cambridge History of India. Cambridge University Press, 2010.